Top 25 Cubs prospects: 2022 midseason update

Lance Brozdowski is a player development analyst for Marquee Sports Network. Below is Lance’s list of the top 25 Cubs prospects as the Cubs near the end of the 2022 campaign. For more on the Cubs prospects all year long, follow Lance on twitter @lancebroz.

As each update of this list comes, the closer Cubs fans get to an incredible wave of talent. The system is highlighted by depth rather than crazy top-end upside. The number of players they have who project to be starting major leaguers in some capacity is equal to if not greater than any other organization in MLB. That’s due in part to the acquisition of talent during the 2021 deadline, 2022 deadline and drafts in each of the last two years.

Now comes the hard part – development. A complex system of strength and conditioning, on-field skills development on both sides of the ball and perhaps the most undercovered element by a mile – mental maturation and development. Multiple departments led by some of the smartest minds in baseball tackle this long-term puzzle with the hope that the organization can improve a player’s top-end projection or raise a player’s floor. The result will be measured in All-Star selections, the amount of wins above replacement (WAR) and, of course, World Series championships.

Below, you’ll find “Stuff+” grades for each pitch type in a particular pitcher’s repertoire. Put simply, Stuff+ is a way to grade the raw characteristics of a pitch where 100 equals MLB league average. (For a more in-depth rundown of Stuff+, head to the bottom of the article.)

Here’s a rundown of the list before we dig in player by player:

- Brennen Davis, OF

- Pete Crow-Armstrong, OF

- Kevin Alcántara, OF

- Jordan Wicks, LHP

- Owen Caissie, OF

- Cristian Hernández, SS

- Alexander Canario, OF

- Cade Horton, RHP

- DJ Herz, LHP

- Hayden Wesneski, RHP

- James Triantos, 3B

- Matt Mervis, 1B

- Benjamin Brown, RHP

- Caleb Kilian, RHP

- Ed Howard, SS

- Miguel Amaya, C

- Ryan Jensen, RHP

- Daniel Palencia, RHP

- Drew Gray, LHP

- Jackson Ferris, LHP

- Yohendrick Piñango, OF

- Moises Ballesteros, C

- Kohl Franklin, RHP

- Jeremiah Estrada, RHP

- Zac Leigh, RHP

Check out past lists:

Top 25 Prospects: 2022 preseason

Top 20 Prospects: 2021 mid-year rankings

Top 20 Prospects: 2021 preseason

1. Brennen Davis, OF

The gap between Davis and the rest of the Cubs prospects entering this season was clear to almost everybody in the industry. So any decision to push PCA above Davis has to be more about the performance of PCA rather than the back injury that led Davis to have surgery in late May. To think that just because the injury has the word “back” in it warrants more of a downgrade than another kind of issue, to me, feels brash.

When Davis was healthy, he was an exceptional offensive threat. He did it in the Futures Game. He did it across three levels in 2021. And the batted-ball data backed it up every step of the way. He’s not going to wow you with massive exit velocities, but as we’ve become more comfortable with the value of hitting a baseball square and optimizing attack angle (more info here), I think Davis is a guy who would pop on both those metrics. Even if he’s slowed down as his body has filled out, it’s a power-hitting corner outfield profile with a prime mix of bat-to-ball, approach and pop. He’s even made subtle adjustments with his hands from level to level, which to my knowledge were all player-driven.

For me, removing Davis from the top requires a clear downtick in on-field performance and batted-ball data over anything else. And we should get a better look at him this fall. A major league spot come 2023 seems imminent.

2. Pete Crow-Armstrong, OF

Notable Stats

Average Exit Velocity: 87.7 MPH

MLB average: 88 MPH

Max Exit Velocity: 109.8 MPH

MLB average: 111 MPH

My perception on PCA over the past year has changed from a offensive projection standpoint. I initially considered him an elite outfield defender, who if he got to a league-average OBP, would be a perennial 3-4 WAR player. That’s why I confidently ranked him No. 2 in the system heading into this season. I never really thought that approach would change, and based on his performance this year, I am wrong. But perhaps the most impressive part is that he’s become more aggressive and is hitting the ball exceptionally hard, creating more tolerance for the approach.

Heading into the final month of the season, PCA was swinging at over 60% of the pitches he has seen since his promotion to High-A. At the major league level this year, among players with over 500 pitches seen, there were only 7 players in baseball with a swing clip over 60%. Just 3 of those 7 hitters are league-average bats. And as you can see in the batted-ball data above, PCA is nearly a major league hitter in terms of how hard he’s hitting the ball (albeit against High-A pitching). That combination is deadly, but projecting ahead for PCA is a complex exercise.

If the approach is this aggressive in the majors, I think it could dampen the offensive upside and create some extended slumps. (There has been some great writing this year on the value of the take.) But we’ve also seen a much less aggressive PCA be exceptionally valuable in the low minors. Regardless, I think the chance PCA ends up with multiple 20-homer seasons is higher than it has been at any point in his career. The swing changes he underwent are working from a “maximize his opportunity to miss” standpoint, which you can watch him talk through here. And one can dream on a truly dynamic combo where he continues to hit the ball hard on a narrow window of pitches he knows he can do damage on and refines his aggression. If that happens, everybody in the industry is too low on him. My projection right now is for him to stay aggressive through the higher minors and into the major leagues. It feels like a conscious adjustment to me based on how hard he’s hitting the ball.

On the defensive side of things, the only thing I need to do is link you to a few of his incredible plays this season: slam into the wall, sliding to his left and going deep over-the-shoulder to his right. He’s going to light up Statcast catch probability metrics because of how well he covers ground. Get ready.

3. Kevin Alcántara, OF

Notable stats

Contact Rate: 50%

MLB average: 37%

Max Exit Velocity: 113.7 MPH

MLB average: 111 MPH

Alcántara’s first season in full-season pro ball has been productive. Maybe he hasn’t stolen all of the Cubs prospect headlines like Alexander Canario and Matt Mervis, but he’s been steady, he’s hitting the ball extremely hard for the level and is still showing a sky-high ceiling all around in his profile. (Oddly enough, the most underrated part of his game might be his speed.) But ultimately, the 20-year-old’s adjustments to High-A and Double-A in the coming years will give us a very good understanding of how much potential he’s destined to tap into.

At the moment, Alcántara is presenting a profile that suggests he’s a plus game power bat with a slightly below average hit tool. This lines up with something like a .240-.250 hitter with a mid-20s homer total. His tendency to chase out of the zone is right around average for the level, maybe a bit high, but the most encouraging sign is his contact rate, which sits about 15 percentage points higher than the average for Class A. The only concern for Alcántara is an extended stretch of limited slugging percentage that extends from early July to mid August. This could be tied to fatigue. A note from some of the Cubs strength folks internally suggested that really lean players like Alcántara wear down late in seasons due to the lack of energy reserves. The drought to finish 2022 may linger a bit recent in the memory heading into the offseason, but it shouldn’t given the beginning of his season was so good.

The biggest variable in his profile, however, is how his body develops. If the goal is to get him to 225 pounds, I don’t think it’s something that happens in one offseason. It’s a bit more gradual of a build over time. But as I mentioned in the beginning of this blurb, the most impressive and underrated thing about Alcántara is his speed. It might be his size that dampens the speed reports on Alcántara industry-wide, but Alcántara’s raw speed and explosiveness stands neck and neck with Crow-Armstrong’s. Yet, you will likely always see PCA graded out as a better or faster runner.

My ultimate projection on Alcántara is a longer development track than some may expect; he’s not going to move through the system like a PCA has. The fruit at the end of that track, however, will be one with big power and probably a higher level of baseline swing-and-miss due to the length of his body and limbs. Some speed deterioration will probably come with a 220-pound frame (it will be harder to move more weight) but there’s a chance he ends up in the Oneil Cruz territory of size-speed-power combination (Cruz is listed at 6-foot-7, 210 pounds).

4. Jordan Wicks, LHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 128

Changeup – 101

Slider – 169

Curveball – 68

Sinker – 31

Wicks still remains my favorite pitcher in the Cubs organization, a title he has held since he was drafted in the 1st round of 2021 out of Kansas State. This is primarily due to the floor he possesses thanks to three above-average pitches in his four-seam, changeup and slider. The wild card is my long-lasting hope that he adds some velocity, which would jump his major league strikeout potential considerably.

The key difference between the college version of Wicks and the Cubs version of Wicks is a new sweeping slider. The pitch grades out as his best offering from a “stuff” perspective and has nearly matched his changeup’s swing-and-miss rate in the minor leagues this year. But despite the eye-opening stuff rating, his changeup is still probably his best pitch, given his ability to generate swing and miss while keeping the pitch in zone considerably more than his slider.

The two characteristics that predict changeup success the most at the major league level are how much more the pitcher’s changeup drops relative to his fastball and how much slower the pitch is. Contrary to what many might think, the drop difference between the two pitches matters more than the velocity difference. The most common changeup, like Wicks’, has a good amount of velocity difference (9 mph) and drop difference (10 inches).

Wicks’ changeup has actually improved its shape compared to last year. He is creating about 2 inches more separation between his fastball and changeup than he did last year and that has helped the pitch maintain its success against much better hitters after his Double-A promotion. His fastball has a good amount of “ride,” which is scouting lingo that describes a pitch’s ability to defy gravity due to the backspin of the ball. He also added back the sinker that he scrapped heading into this season sometime in July, but it’s hard to envision him throwing it a lot when the success of his four-seam is so good.

Wicks’ feel for the zone and execution is the best in the system for the level of “stuff” he possesses. Some of the biggest gains in results based on velocity come once a pitcher starts to cross the 93-94 mph threshold. Wicks currently sits around 92 mph. Adding a few ticks — even at the expense of some command — would vault him into front-line starter territory.

5. Owen Caissie, OF

Notable Stats

Contact Rate: 45%

MLB average: 37%

Max Exit Velocity: 113.4 MPH

MLB average: 111 MPH

In short, Caissie’s bat is fantastic. He has a polished approach for a 20-year-old in High-A, with a chase rate 5 percentage points below the average for the High-A level. After a rough April, Caissie has been a stalwart since. You’ll see Caissie’s contact rate and max exit velocity are very comparable to Alcántara’s, along with a lot of his other underlying batted-ball metrics. But note that Caissie is doing it at a much higher level and has a much more polished understanding of the zone. He’s arguably the best young bat in the system, behind only Brennen Davis.

One key difference in the profiles of Alcántara and Caissie is that Caissie doesn’t project as well defensively and doesn’t have Alcántara’s crazy speed. So the hit tool and power combo here has to continue to grow in order for this mix to work at the major league level. And for now, I see no reason to believe that won’t be the case. There isn’t really a hole in Caissie’s swing. He had a stretch this season where he covered breaking balls incredibly well on the inner third. He’ll probably always struggle with left-handed pitching because of the angles most lefties create, but even there he doesn’t look like a massive liability even if he’s on the strong side of a platoon when he breaks into the majors.

Even if Caissie has a higher probability to actually have some kind of major league role because the bat is so good, Alcántara edges him out because the upside case is better. Is there a chance the defense improves in a corner outfield spot such that he’s viable in right field because of his arm strength? Sure, and there’s no reason to move him off of the outfield until the last possible moment (think about how long Vladimir Guerrero Jr. stayed at third base until he became a full-time first baseman).

6. Cristian Hernández, SS

Notable stats

Chase Rate: 21%

Class A average: 33%

Max Exit Velocity: 108 MPH

MLB average: 111 MPH

Talk to any individual in another organization that has seen the Arizona Complex League Cubs play this year and they’ll tell you to keep an eye on Cristian Hernández. The Cubs internally can’t stop talking about him and neither can other teams. There is no other player in the organization that has Hernández’s upside if everything clicks.

Instead of being aggressive ranking Hernández, I’ve taken a more calculated approach, not having him Top 5 on any of my lists since he was acquired. That’s due in part to a calculation of the probability between his upside and risk. Because of his age and some of the contact issues he’s showing against Complex League pitching, there’s a better chance than some that his development takes longer than expected, like I mentioned for Alcántara above. I’m more comfortable jumping his rank up if there’s an offseason where his game develops considerably than assuming that his body, skills and bat-to-ball ability all blossom at the same time, which would warrant a rank above Davis and PCA.

The singular thing that makes Hernández’s profile stick out at this age is how hard he’s hitting the ball. At just 18 years old, Hernández’s average and max exit velocity are impressive. He doesn’t hit the ball on average as hard as catching prospect Moises Ballesteros (who you’ll read about later on this list), but his top end max exit velocity is higher, and Ballesteros is already in Class-A. Although his frame is slight and he came to the States with little physical maturation, his actions are smooth and his swing doesn’t appear on the surface to need a complete overhaul. Even if Hernández is tapping into some of this power by pulling the ball a ton, where exit velocities tend to peak. It’s still impressive.

From looking at the data, it’s clear Hernández struggles on occasion to make contact in the zone. This is different from the strike zone knowledge issues that a lot of overly aggressive 18-year-olds come to the United States with. Swinging more won’t necessarily hide the issue like it may for a player with great bat-to-ball ability. The fix for this may come down to something more mechanical or related to his attack angle than just understanding where he does damage. And with individuals like Justin Stone (Director of Hitting) and Steven Pollakov (Assistant Hitting Coordinator) in the organization, I doubt they’ll run into issues fixing this blip on the radar. It’s just a matter of when to broach a change or focus on this. There are key body development barriers to cross, which individuals like Cory Kennedy (Head of Strength and Conditioning and Performance Science) will have a field day planning and executing, and he also is away from the Dominican Republic for the first time in his life.

Time can solve all things and there’s a lot of it before the Cubs feel any development pressure to progress Hernández’s game. I don’t think there will be much of a difference in the talent he’s facing between the Complex League this season and Class-A Myrtle Beach next year. The big test of his changes will be sometime in 2024 when he likely ascends to High-A.

7. Alexander Canario, OF

Notable stats

Average Exit Velocity: 87.7 MPH

MLB Average: 88 MPH

Swing and Miss Rate since 6/15/22: 22%

Double-A Average Swing and Miss Rate: 27%

I’m still worried I’m too low on Canario. There’s a case to be made that he’s the third best prospect in this organization, and there’s a strong case that he should be ranked ahead of Caissie, as no player in the organization made more of a striking change in his approach than Canario did this season. Canario went from striking out 32% of the time and walking 7% of the time between April and June, to striking out 18% of the time and walking 16% of the time from July through August. It’s one of the more incredible night-day flips I’ve ever seen and it has vaulted him from a prospect with a low floor and big power to a much higher floor and still the same amount of big power.

There are still some people in the industry that don’t think Canario is going to hit enough to convert on what has emerged as humongous power-hitting upside. But changes like Canario’s refined approach don’t usually feel like blips. Even if he reverts back a bit to around a 20-25% strikeout rate and a 10% walk rate, that would give him more than enough leeway to have an incredibly productive major league profile. The comp I like a lot is an outfield version of the Arizona Diamondbacks Christian Walker. In 2019, Walker hit 29 home runs with a 26% strikeout rate and an 11% walk rate. This year, Walker should hit over 30 home runs with a strikeout rate down around 19%. And he did it by simply swinging less at pitches he couldn’t do damage on – those out of the zone. It’s reminiscent of what Canario has done this year, and although Canario isn’t doing that at the major league level, the quality of pitching at Double-A is great. As he ascends to the majors, the top end stuff will get better, and we’ll see how disciplined he remains.

In talking to major league players this year who have stopped swinging as much and subsequently have performed better (the Dodgers’ Gavin Lux, White Sox Andrew Vaughn and Orioles’ Adley Rutschman are three conversations I’ve had on this topic that stand out), the consistent theme is a realization that they were swinging at pitches which they couldn’t do damage on. “Found my window to swing,” is a phrase I’ve heard multiple times. If this was a more directly trainable characteristic, I think teams would absolutely hammer it, like most have done with velocity on the pitching side. But it appears to be more of a player buy-in, mental maturation model.

Based on the Giants’ desire to roster players who understand the strike zone, they’d likely want a redo on this trade right now.

8. Cade Horton, RHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 155

Slider – 143

The Cubs surprised everybody by drafting Cade Horton 7th overall in the 2022 First-Year Player Draft. Their bet on the quality of his stuff in his final collegiate starts of 2022 connects strongly to the idea that the quality of a pitcher’s stuff stabilizes, or becomes predictive of future success, quicker than almost anything else. Horton has elite underlying characteristics and results on his slider. The floor here, like for Wicks, is extremely high.

Tommy John surgery limited Horton to just 53.2 innings this season for Oklahoma, where he posted a 4.68 ERA. But the Cubs probably care more about the 5 postseason starts where he had 49 strikeouts to just 6 walks on the back of his evolved slider. In his final 5 starts, Horton’s slider routinely had 9-plus inches of horizontal movement between 85-89 mph. This puts him in a elite tier of slider shape. Among all the sliders thrown more than 100 times this season that average 85 mph or greater, only about 13 are getting greater than 9 inches of horizontal movement on average. It comps well to the sliders of Carlos Rodón and Yankees right-hander Clarke Schmidt.

Horton’s fastball possesses a bit of “cut-ride” action to it, meaning that he’s able to get the Wicks’ style carry or lift that makes fastballs so successful at the top of the zone, but it doesn’t run in to righties much. The pitch is similar to the fastballs that Keegan Thompson and Justin Steele throw. They tend to induce weak contact rather than whiffs. Generally, for pitchers who can turn over breaking balls like Steele, Thompson and Horton, being able to pronate – imagine the hand motion required to pour out a glass of water – to create carry on fastballs, run on sinkers or depth on changeups is difficult.

If his repertoire is to evolve, it’s likely going to mean adding a cutter that would grade out very well on the stuff side of things. Coming off Tommy John, Horton may not move through the system as fast as Wicks has, but it shouldn’t be long before he steps on the mound at Wrigley Field.

9. D.J. Herz, LHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 94

Changeup – 93

Curveball – 80

Herz’s 40% strikeout rate last season between two levels as a 20-year-old is still silly to think about. He’s an example of why looking purely at one metric, like his “Stuff+” above, doesn’t tell the whole story. His crossfire delivery creates weird angles for hitters and as a result, models will probably always have a bit of trouble capturing why he has consistent success. There’s some reliever risk here, but the development of his body over the last year has the velocity on its way.

Herz stayed in Arizona for the offseason last year as one of the Cubs invitees to their novel prospect development camp. The results were fantastic, as he put on 10 pounds and was sitting around 197 pounds heading into the season. He had a goal to sit 95 mph on his fastball this season, which would have quickly pushed his Stuff+ grades over the MLB average benchmark of 100. Velocity is not the only variable, but it’s the most important in any quality-of-stuff calculator. And it’s clear the Cubs both understand and want Herz to throw harder.

Unfortunately, Herz’s velocity hasn’t ticked up that much this season. He’s still hanging around 92 mph, but he is up slightly when comparing the first 2 months of the season to his recent promotion to Double-A.

If you give 2 mph of average velocity to everything in Herz’s repertoire, his Stuff+ grades would look like the following… Four-seam: 114, changeup: 101, curveball: 108.

Even without those extra two ticks, Herz’s ability to turn over a changeup is advanced, separating well from his fastball on both speed and drop. His curveball doesn’t possess a ton of depth, but he throws it hard which helps the pitch work wonders on left-handed hitters and down-and-in to righties. He doesn’t have an outlier natural ability to spin the ball and create big horizontal movement at high velocity like Horton, but it still feels to me like there’s a slider in his future, especially given how few pitchers’ primary breaking ball is a curveball in today’s game.

From a development standpoint for Herz, it’s all about the body. Even though he’s older than Horton and just a year younger than Wicks, his athletic age (or the time he’s actually spent on advanced strength programming) is younger than both. This is due in part to him coming into the draft as a high school talent and the other two pitchers above him spending 3 years under the tutelage of Division 1 programs. That means both potential and variance for Herz, but the raw materials are very much there.

10. Hayden Wesneski, RHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 77

Cutter – 121

Slider – 147

Sinker – 92

Changeup – 120

Wesneski is reunited in Chicago with a pitching coach of his from the New York Yankees organization, Daniel Moskos (currently the Cubs assistant pitching coach). The only concern in his profile is the playability of his fastball against MLB hitting, but his execution of the pitch so far in his career has been fantastic. He’ll likely break in as a multi-inning reliever, but his future is a starting pitcher that has the stuff to carve out a rotation spot and hold it for years to come.

The stand-out pitch in Wesneski’s repertoire is his sweeping slider, which averages 18 inches of horizontal movement. This amount of sweep above 80 mph is really only seen in relievers, but it comps well to Toronto Blue Jays’ starter Alek Manoah’s dominant slider. His cutter is a pitch I really like — it grades out well on the Stuff+ side of things and induces a lot of weak contact. I expect it to be an important piece of his weak-contact-generating repertoire. His sinker works inside well to righties and his changeup grades out surprisingly well despite not really having the best feel for the offering (it’s in the strike zone the least amount of all his pitches, by a lot).

Wesneski is a nightmare for right-handed hitters, with his two best offerings moving away from righties. When he’s matched up with lefties he likes to work east-west, hammering pitches backdoor and then coming far inside with his four-seam fastball. Because of his ability to spin breaking balls so well, he isn’t able to generate that carry or ride you’ll see in a four-seamer like Wicks’ (see Horton’s blurb above). As a result, the quality of his four-seam suffers, but the way to make a non-elite four-seamer work is to execute the pitch properly, which Wesneski has done with flying colors.

If he maintains his ability to spot his four-seamer against major league hitters, I see no reason to believe Wesneski isn’t chewing up bats left and right. There isn’t much development to be done here, and maybe it isn’t an ace profile, but this is an arm with great stuff. There’s also the intangible of Moskos having Wesneski’s buy-in given their prior relationship, which I think will work wonders for maturation and sequencing against better hitters.

TIER BREAK

In making this list, I basically drew a line between the Top 10 prospects in this system and the next 15. The way to interpret this break is that the difference between No. 10 and No. 11 on this list is larger than the difference between No. 10 and No. 7 or No. 11 and No. 14.

11. James Triantos, 3B

Notable Stat

Contact Rate: 50%

Class-A Average Contact Rate: 33%

There was almost no universe in which Triantos ascended to his first full-season of pro baseball and his stats didn’t look as rosy as his .594 SLG in a 23-game sample of Arizona Complex League at-bats. But he’s done a great job of maintaining his performance as much as possible while catching a bit less luck on his batted balls (the Arizona air does wonders on fly balls that are outs in any other park). Triantos’ game is built off an fantastic ability to make contact and it will carry him through the minor leagues.

Comparing Triantos to Nico Hoerner makes a lot of sense from a flat swing (attack angle, specifically) and approach standpoint. Even if Hoerner was a college bat and Triantos comes from a Virginia high school, the ability to cover fastballs with good vertical movement at the top of the zone and eliminate the up-and-in right-handed hole many hitters face creates a direct line between the two hitters. His swing-and-miss is below average for the Class-A level and his chase rate is actually around average, suggesting that he is probably swinging a bit too much out of the zone. His ability to make contact is so advanced that it renders his chase rate a bit irrelevant until he faces better pitching.

Triantos’ defensive upside is more of a wild card, giving the total package a bit more risk that I initially expected when ranking last year. The bat doesn’t fit the mold of a major league third basemen, even if his arm strength is good enough to keep him there. The profile is a prototypical second baseman, but with teams preferring to move towards some power upside at the position, it makes it more likely that he’s some kind of utility man who can play third, second and potentially some outfield.

12. Matt Mervis, 1B

Notable Stat

Swing and Miss Rate: 24%

Triple-A Average Swing and Miss Rate: 26%

Mervis has a clear case for being the breakout prospect of the season for the Cubs. Drafted as a two-way player out of Duke University, he’s blossomed into a power-hitting machine, with some astronomical numbers across three levels this season. He’s also somehow dropped his strikeout rate at each level, which really raises the floor on his profile. It’s a left-handed hitting, first-base profile, so the upside is pretty limited in terms of the overall ceiling, but the floor is very high. He’s destined to make some kind of major league impact next season.

Mervis doesn’t jump out on exit velocity leader boards — he’s currently sitting right around or slightly below major league average when looking at his full season of batted balls. He has some balls up above 109 mph, which would put him right around major league average for max exit velocity. His relatively level swing does create some weak-hit infield flies, which lowers his average exit velocity to below the major league average. There’s a trade-off with the flatter attack angle however, that allows him to cover a lot of the high “carry” four-seam fastballs which have taken over baseball in the last few years.

Would you like to see higher baseline batted-ball stats? Sure, but I think he’s a player who will post a ton of barrels – the ideal combination of exit velocity and launch angle – rather than pop on the exit velocity leaderboards. And based on his production, it’s clearly a good enough approach to work against better pitching. He’ll be a nice addition to an otherwise contact-heavy Cubs major league lineup without sacrificing too much on the strikeout rate side of things.

13. Benjamin Brown, RHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 124

Curveball – 149

Slider – 100

The Cubs are the beneficiary of a Philadelphia Phillies system that had room to move a good arm due to the depth of their pitching. It came in the form of trading David Robertson for this 6-foot-6 right-handed pitcher. Brown’s fastball is currently his best pitch and he mixes it in with a pair of breaking balls that are intriguing, even if my expectation is that they’ll look different come next season. I think the Cubs have every intention of seeing him through as a starting pitcher.

The industry seemed a bit slow to catch on to Brown’s development this season, as he’s been ranked conservatively until many industry lists were updated after the midway point. Both of Brown’s breaking balls are moving different compared to last year. In 2021, they both averaged over 6 inches of horizontal movement, with the primary separation between the two coming from how much more his curveball dropped. This season they’re both averaging under 3 inches of horizontal movement and that separation has blurred slightly, but it’s still there when looking at the plot of every breaking ball he’s thrown this season. Because he spins both above 85 mph, the lack of movement doesn’t matter much at all, and the swing-and-miss rate on both sits right above the average for a breaking ball at the Double-A level (37%).

From a development standpoint, the Cubs are likely acquiring Brown with the intention of changing things. Talking to multiple coaches in the organization, my guess is that they think his curveball should be generating more vertical drop without sacrificing any velocity. And I think they see his slider as a pitch that’s due for more lift and carry, again without sacrificing velocity.

Although there are reports Brown’s fastball plays down because of the downhill angle he creates, one thing that’s always stuck with me from a coach in another organization is the idea that vertical movement, or that raw carry regardless of the angle it’s coming from, matters more than anything aside from velocity, for fastball quality. Brown throws his 95 mph on average and has good vertical movement. My expectation is that it shouldn’t be an issue at any level.

There’s also a wild-card in Brown’s splitter, which was converted from a changeup last offseason. The oddity is that the pitch hasn’t been thrown once this season. If it’s something the Cubs decide to bring back into his repertoire, he’ll be even more difficult than he already is on left-handed hitters.

14. Caleb Kilian, RHP

Stuff+

Sinker – 68

Four-Seam – 83

Cutter – 123

Curveball – 57

Changeup – 93

Kilian had a rocky debut at the major league level and has subsequently had very unexpected control issues at Triple-A. The foundation of a starting pitcher has always been here, it’s just one that relies on location more than anybody on this list. So the lack of that command, I think, has a more drastic effect on his results. But as with most analysis, the larger sample is generally more predictive of the future than a small recent bucket of data. And that larger sample says he’s a sub 2 BB/9 pitcher in spades, which should absolutely play at the major league level in some capacity.

You’ll notice above that the only pitch considered major league average by a Stuff+ calculator is his cutter. This is partially because a Stuff+ calculator is going to heavily favor whiffs at the expense of command for a pitch. This is because that individual pitch result is the most predictive and beneficial of nearly any outcome. And as we know, Kilian is a control-based pitcher. So there should always be a disconnect between stuff and Kilian’s actual results.

So how does Kilian get back to the starter who carved through a good lineup in the Arizona Fall League championship game? I think there’s a chance Kilian’s repertoire is reduced down to sinker, cutter and a slider that creates some lateral movement going away from right-handed hitters, which would actually create profile a bit like a lighter version of Hayden Wesneski. Kilian is not done developing, and as we all know, player development is not linear. My readjustment on his rank is more other players popping above expectations and new additions rather than a downgrade in Kilian’s actual potential, which I think remains unchanged – he’s a back-end starter.

15. Ed Howard, SS

Notable Stat

Average Exit Velocity: 89.5 MPH

MLB Average Exit Velocity: 88 MPH

Howard underwent hip surgery in May after a freak play running through first base. There were clear signs of a breakout coming before the injury, particularly in how hard he was hitting the ball in the small sample of balls in play (60). The only problem is that Howard was making a lot of ground-ball contact with that exit velocity spike. This rank is a bit of an assumption that he’ll come back healthy next season and that he’ll eventually start to lift the ball more, a project that I imagine would’ve been coming down the pipeline given health this season. If he’s able to maintain his ability to hit the ball hard once he adjusts his approach to the ball, the ceiling we all expected of Howard starts to come into focus.

There really isn’t much to update on Howard aside from the impressive batted-ball numbers mentioned above. There’s some swing-and-miss in his game, but there is also developing power. If his defense keeps him at shortstop, it creates a lot of tolerance for a more aggressive approach, especially if he continues to hit the ball this hard. If he moves to second or third base, the offensive bar changes, rising for either spot but particularly so for third base.

Keep in mind that Howard’s 2023 will be just his age-21 season, and if he would’ve progressed through High-A without issue, there’s a chance he could’ve been a 20-year-old up in Double-A before the end of this season. Instead, he loses some development time because of the hip, but his timetable is still attractive from a development standpoint.

16. Miguel Amaya, C

Notable Stat

Chase Rate: 24%

Double-A Average Chase Rate: 24%

Amaya, like Howard, has lost time this year and last year due to Tommy John surgery. He’s back purely as a designated hitter right now and his batted ball data looks good for Double-A. He’s creeping up above major league average in terms of average batted ball velocity and his top-end swings look good too. The results may not be eye-popping yet, but remember that he has less than 60 games played since the COVID-19 shut down in 2020. If he’s a catcher, the offensive potential is high enough for the profile to work.

Multiple questions still exist with Amaya’s profile. Will he actually catch in the majors? Does he tap back into power that seemed to phase out prior to this surgery? Is there enough of an offensive floor if he doesn’t stick at catcher? And because of those questions, he’s not going to soar above a lot of the new acquisitions in the Cubs organization, who are in more of a helium phase given organization switches that could help their ultimate potential.

Amaya is a strong candidate along with Brennen Davis to represent the Cubs in the Arizona Fall League with the Mesa Solar Sox. Even if he’s still not catching at that point, the ability to make up development time offensively is huge.

17. Ryan Jensen, RHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 130

Sinker – 86

Slider – 156

Cutter – 106

Curveball – 85

Changeup – 110

Jensen was one of the most difficult pitchers to rank. Right as I started to think about ranking pitchers in this system, he went on the development list for five weeks and returned a very different pitcher. He shortened the “takeaway” portion of his delivery, which results in a more acute angle between his forearm and bicep before his arm unravels and releases the ball (you’ve likely seen this before with Lucas Giolito and Shane Bieber). But perhaps even more important is the fact that he hit 100 mph after the change and has finally developed a slider that stuff metrics like, along with a nasty new cutter. I’m betting on the new stuff ratings here, regardless of prior performance.

In my past write-ups of Jensen, I dubbed his sinker a “turbo sinker” and a pitch that he could survive at the major league level with even if he threw it 70% of the time. That assessment was incorrect. After coming off the development list, Jensen actually started throwing his four-seam fastball more than any other pitch in his repertoire. And it’s primarily because the pitch is just better at generating whiffs. I do think this sinker is better than the 86 Stuff+ grade that it has above, primarily because it generates a lot of contact into the ground, which certain stuff metrics don’t value too highly. Jensen also still seems to be more comfortable getting a strike with his sinker than his four-seam, which at the end of the day and render a Stuff+ reading kind of irrelevant.

Fastballs aside, his new cutter and slider are massive upgrades to his repertoire. After years struggling to throw a quality slider, he’s finally found one that can get around 5 inches of horizontal movement and more impressively, sit around 90 mph. He also birthed a new cutter out of nowhere, that’s a barrel-breaking 95 mph on average. There’s also the more anecdotal idea that multiple quality pitches slightly pushes each of them up a bit in quality. And Jensen has 6 legitimate offerings now.

Just when you think you’re out on Jensen because he’s a sinker-first reliever, he pulls you right back in. The new mix feels like that of a starting pitcher and the resulting rank is a bet on his new Stuff+.

18. Daniel Palencia, RHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 175

Slider – 113

Changeup – 60

The Cubs’ acquisition of Palencia from the Athletics at last year’s deadline for reliever Andrew Chafin appears to be a coup. Palencia is one of the loudest arms in the Cubs system, averaging 97 mph on his fastball and touching over 100 mph this season with a hard slider and a raw changeup. He has the best fastball in the Cubs organization. And if he’s able to find the zone more often, the sky is the limit.

It’s clear the Cubs have been trying to simplify things for the 22-year-old righty. For the first two months of the season, Palencia threw 2 pitches exclusively: fastball and slider. In June, the organization started to bring back his changeup, which he’s able to separate velocity-wise from his fastball by about 10 mph but not able to create a drop difference that allows the pitch to grade out high per Stuff+. The pitch is rarely in the zone but against High-A hitters who are trying to get a visual on his fastball and slider, it generates ugly out-of-zone swings.

Palencia still has two more pitches to bring back if the organization sees the cutter and curveball he threw in 2021 as viable future offerings. But for now, his bread and butter is his elite fastball and a hard, bullet slider that stymies hitters. With the buzzword being “sweeper” in this organization and others, Palencia’s slider is on the other end of the spectrum, spinning like a bullet and dropping rather than sweeping away from right-handed hitters. These kinds of sliders actually generate swings against it that look more like a hitter is seeing changeup than slider. This is due in part to the expectation that a slider will move away from you with some kind of horizontal movement, but instead a slider like Palencia’s will stay true and almost appear to fade down and in on your hands.

The only issue with the entire package is Palencia’s ability to put his pitches in the zone — he doesn’t throw a lot of strikes. His slider is out of the zone nearly 60% of the time and his fastball is a coin flip. It seems like the Cubs are using a simplified targeting strategy with Palencia, where the catcher just sets up over the plate most of the time aside from assuming Palencia can pick corners. But I’d love to see more commitment to the strategy, like the Rays organization does at every level (more on that targeting idea here). This is especially true for a pitcher like Palencia, where his stuff is so good, it’s not going to get hit in the zone.

It could also be the case that a guy like Palencia who throws this hard and moves this fast, just never develops the ability to control where his ball is going, which is true of a lot of hard-throwing arms that end up in the bullpen. Double-A will be a huge test for the righty.

19. Drew Gray, LHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 85

Slider – 127

Curveball – 57

Changeup – 99

Gray went down with Tommy John surgery in March of this year after demolishing the Arizona Complex League in a small sample. According to rumblings I’ve heard, the majority of his focus during rehab has been gaining strength to bump his velocity up past the 90 mph he sat in his 4 innings of work right after being drafted in 2021.

There really isn’t much to update here on Gray. He started throwing again on July 11th and as one individual in the Cubs organization put it to me earlier this year, “We’re at the point in baseball where TJ isn’t a big deal beyond the developmental time lost.” And Gray doesn’t turn 20 years old until next May.

The key thing about Gray that stands out is how flat his fastball approaches the zone, due in part to how much “carry” he’s able to get on the pitch from a low release height. Generally, that desirable backspin is found in pitchers like Wicks. Because of Wicks’ over-the-top release, it naturally sets up his hand to get directly behind the baseball and create that true backspin. Imagine trying to release a baseball with perfect backspin but throwing side arm. It’s difficult, right? Primarily because you’ll find that you need to really orient your wrist vertically in order to create that Wicks-esque backspin. So pitchers like Gray, who can get some backspin on their fastball from somewhat of a low slot will have a natural advantage with the pitch.

This is a characteristic Gray shares with DJ Herz, who is also able to get his fastball to approach the zone at a very flat angle (more on “flat approach” pitches here). And soon I expect him to be carving just like Herz did. He’s an easy prediction to be a Top 10 prospect in the Cubs organization if his velo ticks up after Tommy John.

20. Jackson Ferris, LHP

Ferris comes without Stuff+ data due to being a high school arm, so there are limitations on how much I can analyze the raw characteristics of his mix before seeing him in the Arizona Complex League. From the incredibly small sample of data I do have, Ferris throws a 93-mph fastball, a mid-70s curveball, and a mid-80s changeup. Nearly all high school pitching prospects are extremely high risk, but the velocity foundation Ferris has bodes well for his evolution as a starting pitcher assuming further upticks with age.

There is some reading between the lines that needs to occur with the selection and subsequent evaluation of Ferris. The Cubs gave him over $3 million to sign in the 2nd round, the highest bonus of any player selected between Pick 24 in the 1st round and the end of the 3rd round (bonuses aren’t confirmed by teams, so this is based on reported figures). I think the Cubs viewed Horton and Ferris as one of the best 1-2 punches possible in the draft. As teams in the NBA have shown with the trading of picks, you just need as many shots in the draft as possible rather than just one pick given the variance in prospects.

Apart from Ferris’s mix, the most distinct element of him as a pitcher is his arm angle. He extends far down the mound and tilts his trunk substantially, allowing for a lower release point than expected for this high of an arm slot. This should allow his fastball to play up above its metrics even if he isn’t ever a pitcher who is getting big carry on their fastball.

I spent a lot of time trying to figure out whether I should put fellow IMG Academy lefty Gray above Ferris simply because of the underlying metrics on Gray’s stuff and his small-sample performance. But I’ll admit that the amount of money the Cubs were willing to give Ferris means they have big expectations and at the end of the day, absent of performance data in pro ball, put me where I am between Ferris and Gray.

21. Yohendrick Piñango, OF

Notable stat

Max Exit Velocity: 113.6 MPH

MLB Average Max Exit Velocity: 111 MPH

For the second year in a row, Piñango pops on the max exit velocity leaderboards among the Cubs top prospects, alongside names like Alcántara, Caissie and Canario. Not only does he hit the ball hard, he also makes an exceptional amount of contact, right around the levels of PCA and James Triantos. The only knock is that there isn’t much of a defense profile, similar to Owen Caissie. He’s kind of an amalgamation of multiple prospects in the system, the result of which is a really fun player that I don’t think gets enough credit for his performance and underlying metrics.

Piñanago’s batted ball data in 2021 was similar to this season and had me expecting the big jump in power output. He’s an aggressive swinger but like multiple other players on this list, he can put bat-on-ball better than most in the system.

There was a point in this process where I had Piñango above Triantos on this list, but I ultimately settled on this arrangement. If anything, I think that highlights the small difference between the future potential of Nos. 21 and 11 on this list, a testament to the depth the Cubs have developed. You could easily put Piñango above the four pitchers ahead of him right now as well, I just think those arms edge out Piñango on an upside basis. If in 3 years it comes out that I was too low on Piñango, I’d like to have this paragraph serve as my ticket to absolve me from blame.

22. Moises Ballesteros, C

Notable stat

Chase Rate: 55%

Class A level Average Chase Rate: 32%

Ballesteros is a glimmer of hope for the Cubs’ catching depth, which is otherwise pretty barren. His body is large, and this rank comes with the hope that he stays with the Cubs this offseason for their second iteration of their prospect development camp this offseason. He projects as a catcher right now, even with the big body, but the more impressive part of his game is a decent combination of power and OBP, which makes him resistant to an eventual robotic strike zone if the league decides to adopt one.

The Cubs internally love the 18-year-old Ballesteros. He was a name initially left off this list until a conversation with an individual on the Cubs player development staff suggested it would be bold to leave him outside the Top 25.

He’s walking above a 10% clip this season which is perhaps a bit high for how much aggression and swing-and-miss there is in his game. Among every player on this list, Ballesteros has the highest chase rate. But he couples it with a great innate ability to make contact, similar in statistics to Triantos.

The warning here is just that catchers take a long time to develop. But if his promotion to Class-A at just 18 years old is any indication, the Cubs think he’s more advanced than his age shows.

23. Kohl Franklin, RHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 166

Curveball – 89

Changeup – 84

Franklin’s 2022 has been a bit rocky on the results side of things, which is forgivable given he had only thrown about 50 innings since being drafted in 2018. For me with this rank, there’s a bit of an assumption that his mix will change after this season, when the focus goes from “just get outs and be healthy” to “let’s make you into a major league arm.” The foundation of the repertoire is built off a great fastball, that averages 95 mph and got up near 100 mph in shorter stints this spring.

In terms of developing his secondaries, I think the focus comes down to his curveball. Even though this is a fine pitch that will likely stay in his repertoire for a while, for a curveball to be a feared offering it almost always has to be thrown hard with a lot of break. As a reliever, maybe this pitch changes for Franklin, but I think the intention here is a starting pitcher. So what do the Cubs do this offseason and into Spring Training? I think it comes down to some kind of slider. Franklin spins his curveball over 3,000 rpm on average where the major league average is about 300 rpm lower. That natural feel for spin almost always will allow a pitcher to develop a lateral breaking ball that sweeps away from righties and has good shape. You could also dream and see some kind of cutter mixed in as well, resulting in a repertoire that looks a modified Keegan Thompson.

The key difference between Thompson and Franklin is that Franklin’s changeup is legit. Despite the grade above, the pitch generates a swing-and-miss rate above 50% and has a clear visual component that I think throws hitters off. So even though it may never show up as an elite offering on stuff alone, like his curveball, I think it’ll always be in his repertoire and be an effective pitch.

My last point on Franklin is that his control is bit of an issue, as he has no pitch that he’s putting in the zone more than 48% of the time this year (major league average for starters is somewhere around 50-51%). If he is to live at that number, he would need exceptional stuff to compensate for the lack of strike throwing. I envision a lot of development to come for Franklin.

24. Jeremiah Estrada, RHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 178

Slider – 147

Changeup – 67

I perennially reserve my final pick on a list for who I think is the best reliever in the Cubs system. With the evolution of multiple stand-out arms in the Cubs system, however, I’ve stacked two of the best I think have the highest chance for impact in leverage spots with the MLB club. Estrada edges out Zac Leigh by a hair on my list due to his huge fastball and unique slider.

Estrada’s fastball averages over 21 inches of vertical movement at 95 mph. That much vertical movement is about 5 inches above the average four-seamer. Estrada spins the ball at a specific direction and rate that allows the pitch to really resist the force of gravity that forces every pitch to drop. This causes it to drop less than you’d expect, resulting in a lot of swings underneath the baseball especially at the top of the zone.

His slider also has a lot of vertical movement and horizontal movement, which is odd for the pitch with as much sweep as he’s able to get. I’ve heard from some coaches that there’s a specific group of pitchers with particular fastball shapes than throw sliders which end up picking up this much “lift” or “carry,” but I’ve been unable to find a reason why this happens with some pitchers and not others, or at least a reason that I understand enough to explain. Regardless, the pitch generates a mammoth swing-and-miss rate above 50% and is a surefire major league offering. I expect him to be at Wrigley soon, possibly working the 9th inning in due time.

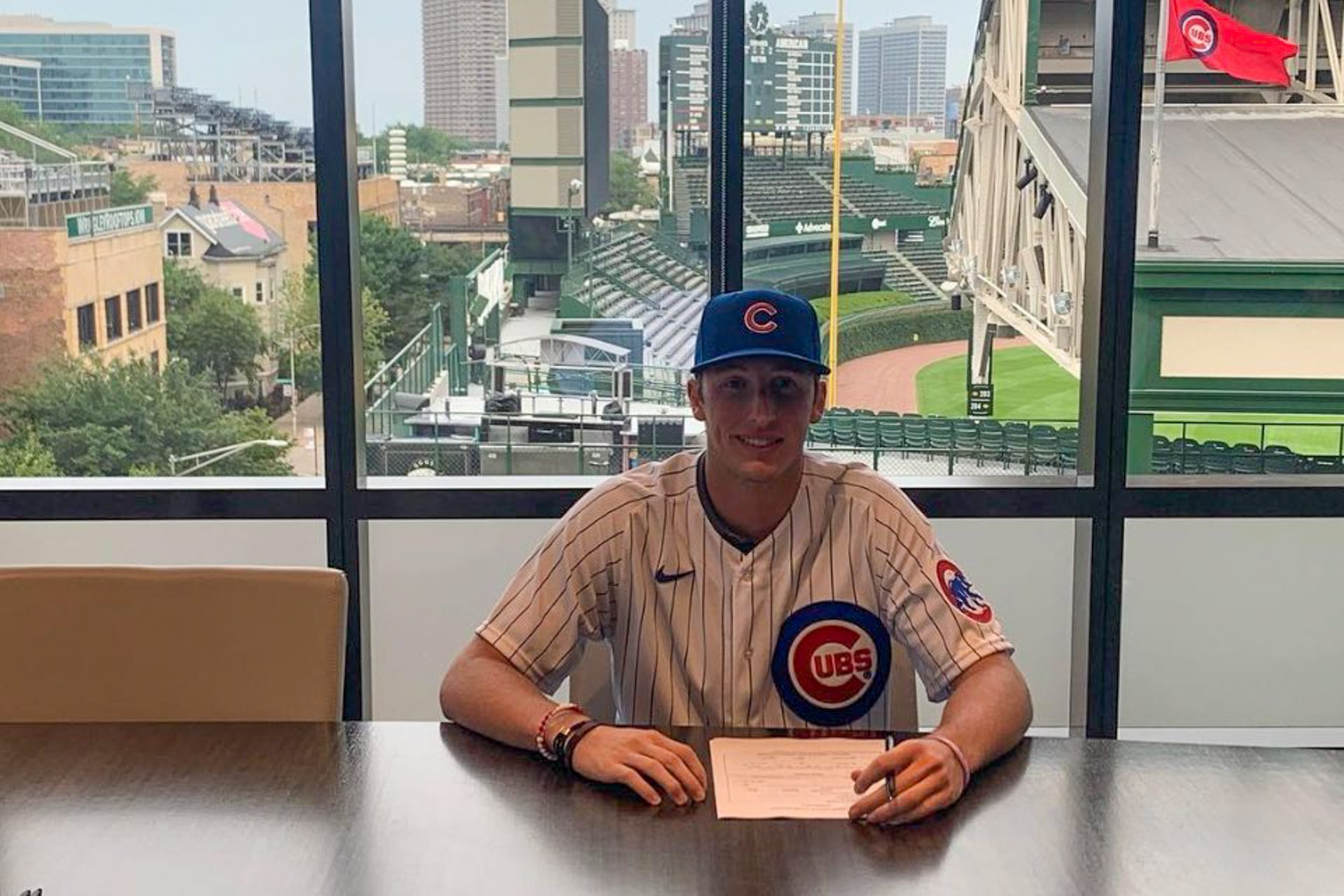

25. Zac Leigh, RHP

Stuff+

Four-Seam – 157

Slider – 162

Changeup – 82

Leigh is a name that drew some interest from other teams in the league to be included in larger deals that didn’t manifest at this year’s deadline. And it’s apparent why. Leigh has a lethal fastball-slider combination. It’s splitting hairs as to whether you’d have Leigh or Estrada holding down the 9th if all goes well from a development standpoint. I’m giving a slight edge to Estrada due to his track record, but Leigh’s recent decrease in walk rate makes me think I could be wrong.

Leigh, like Estrada, gets good vertical movement on his fastball, which allows it to flatten out at the top of the zone and drive hitters nuts. On occasion, he throws four-seamers that take off a ton arm-side and others that kind of cut a bit and take off vertically. The variance and funk in his mix is also present in his slider, which is often called a curveball but based on the average movement of all his breaking balls this year, profiles much more like a slider than curveball.

The exception to this claim is that he does intentionally manipulate the pitch at time to have more curveball shape, which allows it to be a bit more effective versus left-handed hitters (because of the more vertical shape). You’ll see this subtle shape change in a lot of the sliders thrown by Los Angeles Dodgers pitchers, like Blake Treinen. It’s a way to neutralize platoon splits for a pitcher who will probably never incorporate a good changeup into his mix.

Just missed

Kevin Made, SS, is a name that I tried very hard to get on this list but ultimately couldn’t find a way to squeeze him in. The approach for him took a massive step forward. Back in Myrtle Beach, he basically had such aggressive of an approach it was hard to analyze anything about him aside from a contact quality standpoint, which was mixed. But come 2022, he jumped his walk rate from below 4% to over 10%. Most important is that he maintained it when promoted to High-A. He’s a good glove at shortstop as well, but the profile here may be more of a utility player rather than a potential for big impact at any one spot.

Luke Little, LHP, is a big dude. Little’s body comps similar to Ballesteros (apart from their height) and each are obvious candidates to come into spring next year in the “best shape of their lives.” Especially if they are confirmed as names that Cubs will include in their offseason prospect development camp that saw strides in numerous players physically, like Herz, Davis and Kilian last offseason.

Luis Devers, RHP, is another name that I found difficult to get on this list. It was him or Franklin for me based on the structure of my 20-25 ranks, and Devers has exceptional results. But the raw stuff projection isn’t as tantalizing to me, and I’ve been trying to make that more of a driver on my list given how well it correlates to major league success.

Porter Hodge, RHP also fits the Devers mold of a clear snub on this list. He’s throwing a sweeping slider with a fastball that has a bit of “cut-ride,” which has become a major feature of a lot of pitchers in the Cubs organization.

Stuff+

All major league organizations, including the Cubs, have their own model that values elements of a pitch differently (things like vertical break, the pitcher’s release, velocity, etc). It aims to predict how a pitch will fair at the major league level. If a four-seam fastball has a Stuff+ of 120, that means based on historic MLB data, we’d expect that four-seamer to perform 20% better than the major league average fastball. If a slider has a Stuff+ of 95, that means that based on historic MLB data, we’d expect that slider to perform 5% worse than the major league average breaking ball. For the purposes of Stuff+, four-seamers and sinkers are grouped into a bucket called “fastballs,” while curveballs and sliders are grouped into a bucket of “breaking balls.” Changeups have their own bucket and are graded in relation to a pitcher’s primary fastball. Cutters can be in the fastball or breaking ball bucket depending on the shape of the pitch.

Are there limitations? Absolutely.

For one, the particular model I’m using (courtesy of Driveline Baseball) doesn’t do the best job of taking into account players who create average movement/velocity from distinct releases, allowing that movement to play up above its grade. Herz is a textbook example of this, as you’ll see below.

Stuff+ also has no regard for execution or command. For many pitches with average to below-average Stuff+ grades below, if the pitch is executed well, it can play to average or above average levels. This is the case with many curveballs, which Stuff+ models often find it hard to like, but are often used in repertoires purely to help platoon splits or give hitters another look.

Like every statistic, Stuff+ is merely one tool in the toolbox. You can read more about Stuff+ here. If you ever have any questions or don’t understand something, my DMs are open on Twitter.