Top 20 Cubs prospects: 2021 mid-year rankings

As Major League Baseball inches back to a new normal, Minor League Baseball looks on longingly, wondering — for the most part — what normal really is.

The widespread contraction of the minor leagues eliminated Class-A short-season leagues and forced numerous teams into reorganization. Alternate site activity and intrasquad scrimmages provided the only competitive live baseball for most minor leaguers last season.

Some players have reflected positively on specific aspects of the structure. It provided time to foster chemistry between players who are at different points in their development, but we’re realizing now that it has created a development gap between the major and minor leagues.

The gap manifests in the increased walk and strikeout rates, particularly in lower levels like High-A, Class-A and on the complexes in Arizona and Florida. Pitchers’ control is arguably worse than it has ever been in the low minors, hitters’ approaches have deteriorated and defense is below its usual level of aptitude. On top of that, movement from level to level now brings on unique rules as MLB uses the minors as a petri dish to improve play and fan engagement in the majors.

The Cubs activity at the deadline has jolted their farm system into the top half of Major League Baseball (Top 10 by some measures). But the majority of that talent is now in the low minor leagues. While this aligns the debut timeline of a number of the team’s top prospects, low-level talent has inherently more variance than Double-A or Triple-A players because they’re further away from their prime.

Mixing all these variables together — along with a large chunk of Cubs talent existing in the same tier of future impact — makes for more divergent rankings than usual from website to website. Our submission into the prospect cauldron is based on conversations with multiple scouts, team analysts and members of player development in other major league organizations. It also relies on advanced data from the minor leagues — pitch movement profiles, average and max exit velocities, etc. — in an attempt to marry subjective opinions from sources with objective information.

Terminology key:

Plus-plus = two standard deviations above the major league average, “70 grade”

Plus = one standard deviation above the major league average, “60” grade

Above average = between major league average and plus; “55” grade

Average = the major league average; “50” grade

Below average = between major league average and one standard deviation below the major league average, “45 grade.” Despite sounding pessimistic, this could still mean the skill is better than 30-40% of major league players.

Marquee’s 2021 preseason prospect rankings, for reference.

1. Brennen Davis – OF

Davis is a Top 20 prospect in all of baseball. He is also a great player to illustrate that the gaps between numerical rankings (1, 2, 3, 4) are not equidistant. There is a cavern between Davis and the rest of the prospects on this list. That is not an indictment of the Cubs at all, it merely shows that Davis is both really good and the Cubs prospects who build an admirable case of being placed above or near him are young enough that their projection and performance at low levels can’t surpass Davis’ projection and performance against much better competition.

Davis’ swing and miss jumped up upon his promotion to Double-A, which can be partially attributed to the divide in talent the layoff has created between the low levels of the minor leagues. But even with his 30% strikeout rate, Davis has hit 9 home runs and posted an OBP above league average.

To reduce what makes Davis good to as simple a line as possible: he barrels a lot baseballs. The notion that exit velocity and launch angle are overvalued statistics, inundating the sport with more numbers than needed has some merit. But that merit is more from a delivery and communication standpoint than an actual objection to the value of the information.

Balls hit at or above 95 mph with between 26 and 30 degrees of launch angle have a batting average of .686 and a slugging percentage of 2.490 in 2021 (that is not a typo). I’d even argue that this band of launch angle is too small. The idea should simply be to hit balls hard in the air. And any combination of statistics you search for that align with the terms “hard” and “in the air” will lead you to objective information that this is good, and the more you do it the better you will be. There is some concern that Davis isn’t going to appear at the top of max exit velocity leaderboards — which even in small samples is a predictive statistic if a hitter shows an outlier trait — but this just puts a little bit more emphasis on Davis’ approach at the plate or the chance he gives himself to make good contact, rather than relying on massive, outlier scenarios. And the sample of hitters who succeed without crazy max exit velocity numbers — Trevor Story, Nick Castellanos — should ease some minds for now.

Combine the frequency at which you hit balls hard and in the air with an advanced understanding of the strike zone for a 21-year-old who is a plus runner and plays good defense, and it’s clear why Davis is the cornerstone of this farm system.

2. Pete Crow-Armstrong – OF

Crow-Armstrong is a very different prospect than nearly every position player that comes after him on this list. His carrying tool is a future double-plus glove in center field, which would put him around the top 3% of all outfield defenders in baseball, a perennial Gold Glove finalist. His speed is above average and the approach he displayed in an extremely small sample of games before undergoing surgery on his shoulder in 2021 was exceptional, suggesting his bat was already too advanced to be challenged at Class A (this could have simply been a product of poor pitching at low levels, but Crow-Armstrong at least wasn’t fooled by non-competitive breaking balls off the plate).

Crow-Armstrong’s power is the mystery. Some scouts don’t expect anything more than 10-15 home runs per season, even at his ceiling. This has not stopped other hit-first outfielders from producing big power numbers in outlier seasons, but the Harvard Westlake graduate’s profile will shine through his on-base skills and all-fields contact over big power. Some player development coordinators might even favor this kind of hitter. This is due to the difficulty many prospects have recognizing and laying off spin or advancing their understanding of the strike zone, partly because there aren’t clear, objective ways to train many skills in hitting for a variety of reasons.

The lack of power projection could limit his ceiling but it’s hard to find an outfielder with a higher floor than Crow-Armstrong anywhere in the minor leagues.

3. Jordan Wicks – LHP

The Cubs drafted Wicks 21st overall in the 2021 MLB draft. The consensus in amateur draft circles seemed to be confusion as to how the southpaw fell past 15 overall given what seems to be a high floor. Wicks already throws four pitches and sports a sparsely used curveball. His walks have never ticked above 3 per 9 innings in his collegiate career and he will likely move quickly through the minor leagues.

Wicks could have fallen because on the surface, he’s not really what a modern, successful young starting pitcher looks like in a championship-level rotation. Teams covet velocity and wipeout slides, or an equivalent pitch that is unique based on how it’s released (think about every Brewers or Rays bullpen arm), how it moves or some combination of both. But despite the lack of present velocity (Wicks averages 92-93 mph on his four-seam fastball), the vertical movement of the pitch is some of the best in the Cubs system among pitchers with a good chance to start. This means the pitch will have a better chance of success up in the strike zone when compared to a similar pitch with less vertical movement.

On top of his four-seam fastball, Wicks mixes in a strong changeup with more than 10 mph of velocity difference off his fastball. He also has a developing slider, which presently acts more like a cutter around the 85 mph window of velocity, meaning the pitch doesn’t really move much and in a vacuum, more movement leads to more swing and miss. Upon entering the Cubs system, it seems likely this pitch will change into something either hard with a similar movement profile, or the Cubs will work to increase the pitch’s horizontal movement while maintaining its velocity.

4. Owen Caissie – OF

Caissie was a notable omission from our preseason list. He came across as a piece of the Yu Darvish deal but was not billed as the central figure. That was reserved for Reginald Preciado. The omission stemmed from conversations with scouts last year who were not impressed with his performance and didn’t think there was much upside in his hit tools despite the obvious raw power.

Fast forward 6 months and it seems like more scouts contest this notion based on his combination of development, health and performance in the Arizona Complex League, even with a rough start.

Caissie is around 6-foot-3 and his body has matured quickly, putting his playing weight currently above his listed 190 pounds. How he works his hands to get his bat on plane with an incoming pitch is unique. He doesn’t have a hitch, but the movement reminds some of the Dodgers’ Gavin Lux. You can imagine a scenario in a few years where Caissie’s hand movement is reduced to simplify his actions and give him a greater probability of being on time against better competition. He’s not a plus runner and he profiles fine in a corner outfield position, but his profile is carried by the potential for his offensive production.

Caissie’s raw power is some of the best in the system. He has one of the highest average exit velocities and highest max exit velocities this year among the Cubs top prospects. The recurring theme you’ll see in any young prospect with power is simple: will he hit enough to actualize all or the majority of his raw power output (raw power is simply how far/hard can you hit the ball)? The resulting idea, in scouting parlance, is “game power.” The difference in a player’s raw power and game power can usually be attributed to their lack of a hit tool. Players with great hit tools can usually close that gap to almost zero, because their swing and approach allow them the greatest possible chance for contact and they run into power as a result.

Some scouts think Caissie’s swing is long and his levers will limit his ability to get his hit tool to maximize all of his power output (which would result in around 30 home runs at peak). So the result of his game power projection is something in the low- to mid-20s. Others don’t see too long of a swing and are more optimistic about his hit tool extracting as much power as possible. Which side you are on in this subjective argument absent biomechanical data of his swing determines where he lands inside the Cubs Top 10. For us, we think there’s a greater chance that Caissie reaches his power ceiling at the moment.

5. Kevin Alcantara – OF

In conversation with a scout who saw Alcantara as recently as his first series of games with the Arizona Complex League Cubs, the thing that jumps out is his abnormal combination characteristics and skills. He is a lanky 6-foot-6, with above average speed and above average raw power. He has a massive leg kick, with his knee traveling above his belt at the peak of the motion. He also doesn’t whiff nearly as much as one would expect for a player of this size and age.

The question with nearly every sub-20-year-old prospect playing in the Arizona Complex League with a projectable body like this is A) how much weight does he put on and B) how does that affect his speed-power combination, which affects defensive positioning, and as a result, the offensive bar needed to play that position at the major league level. For now, Alcantara seems destined for right field, which sets the offensive bar high.

But the idea that simply adding weight and gaining strength will increase a player’s immediate power output by a substantial margin is flawed because it leaves out the substantially more important question of how efficiently does that player move in space. If you bulk up and the potential energy created in your legs is still inefficiently transferred to your hands and bat, there will be unnoticeable in-game power gains despite the descriptive phrase, “his body filled out.”

Along with plate approach and pitch recognition, this concept of an efficient swing sits at the heart of developing young offensive talent. It will be central for the Cubs to aid Alcantara with his body maturation and how it changes his on-field performance. If there’s synergy, Alcantara will easily become a Top 100 prospect in baseball and Top 3 on this list. The raw output from a data perspective is already there, even if the precedent of a 6-foot-6 hitter not having issues with pitches on the inner third, particularly up and in, is rare.

6. Miguel Amaya – C

The complexity of ranking and evaluating catchers ties directly to the potential of a robotic strike zone in MLB sometime in the next five years. If this happens, the supply of players with a chance to catch will increase, creating a scenario where teams have to evaluate talent without framing. Some analysis suggests the skill of pitch framing has a much wider range of impact on a player’s defensive skill behind the plate than blocking or managing runners. The best framer, for instance, is worth about five times more to their team, on that skill alone, than the best blocker from a run prevention standpoint.

Removing the impact of framing may push teams to prefer a catcher who is average or even below average defensively if they can get on base or slug more than the average catcher, or whatever that new average is. If you’re a catcher with a strong ability to frame and not much else, you will likely be out of a job.

The impact this rule could have on Amaya is somewhere in the middle, but his offensive skillset — especially from a pitch recognition standpoint — is good enough to carry him into a starting major league catcher role of some kind. Even though his profile may not result in multiple All-Star level seasons, the value of a catcher with strong OBP skills and well-rounded defense is continually underrated primarily because the aggregate value at the end of a season doesn’t really compare to the best players in the league.

Amaya’s injuries this season may have clouded our ability to gauge whether he’ll tap into more power at the major league level. Right now, it looks like he’ll end up with his hit tool as his carrying trait. If power does come, it’s the cherry on top of a solid major league profile.

7. Cristian Hernandez – SS

Hernandez was the most difficult prospect for us to place in these rankings because of the small number of people who have seen him play recently. The data he has produced in his DSL (Dominican Summer League) play is very encouraging. He’s on par with bats like Alcantara — if not better — in terms of max and average exit velocity, and making a ton of contact against age-appropriate pitching. If this holds upon his arrival stateside, he will carve out a spot higher on this list.

Hernandez’s bat right now is hit tool over power, as many underdeveloped, young players are. Reports suggest he runs well and has good actions at shortstop, but the development of his body will play a big part in whether he moves off the position. There is enough room to project his bat to survive the offensive bar needed if he moves to third base or a corner outfield spot. But the ideal, high-impact outcome is that he plays well enough at shortstop to stick there, even if his defense at peak is below average to average, and he hits in the .260-plus window with 20-plus home runs.

A standard development timeline suggests Hernandez will play in the Arizona Complex League next season, which will provide a wealth of validation and could separate him further from Howard as the clubhouse leader to be an all-around impact shortstop on the Cubs’ next championship team.

8. Ed Howard – SS

Howard, along with Pete Crow-Armstrong, are players who have value primarily based on their defensive play. He is exceptionally polished defensively for his age, projecting towards future plus defense or better, with a low likelihood to move off shortstop.

His offensive output has more variability. While his swing — like his defense — is quiet and smooth, in his first taste of Class-A pitching, there hasn’t been much in the way of power and the solid bat-to-ball skills he had coming out of high school haven’t shown up yet. The batted ball data has also not been as strong as some other top bats in the system. But it’s likely that Howard’s development has been obstructed, like many others from the 2019 draft class, by the Covid-19 pandemic and reshuffling of the minor leagues.

For a prospect with his pedigree, there’s little doubt his offense will come around. There’s a good chance he ends up modifying the motion of his lower half from his simple foot-down-early toe tap to something that would bring on a greater chance for harder contact. As one current minor league hitting coordinator described the front foot a few years ago, “the pressure [of] shifting onto the front foot is what initiates [the] swing.” The greater time between the peak force exerted by ones front foot and contact with the ball, the possibility grows for a loss of potential exit velocity. But this critique comes with the admission that we on the public side will never have access to biometric data of hitters’ swings to confirm whether what we speculate in a general sense is factually correct for an individual player.

For now, Howard still projects to have an average to above-average hit tool with a chance for below average to average game power. This is more than enough to be an everyday shortstop at the major league level given his defensive polish.

9. Alexander Canario – OF

After the Cubs acquired Canario from the Giants in the Kris Bryant trade, they assigned him to High-A South Bend. It was a relatively aggressive promotion for a player who just turned 21 years old and displayed a high strikeout rate in Class-A of the Giants organization. Canario’s success early with South Bend has proved this was the correct assignment, even if he still carries a high strikeout rate.

His frame (6-foot-1) doesn’t provide a lot of room for projection like Alcantara or Preciado; he’s more like Caissie in terms of his body probably being close to peak size and weight. Any of the gains he makes from this point onward will be related to an approach change or a tweak to the efficiency of his swing (essentially, how well he transfers the potential energy created in his lower half to his hands). Both of which should help with the apparent swing and miss issues.

If you use a tool like Baseball Savant to display the location of pitches where the best power hitters in baseball hit home runs, the majority of those pitches (over 75%) will be in the heart of the strike zone. Canario has no problem demolishing these pitches. But there’s a likelihood that he becomes a player where scouting reports say to throw 60% offspeed pitches and challenge the young righty to lay off bad pitches. Whether he does so against better breaking balls at higher levels of the minors will be the difference between an everyday power-hitting outfielder and more of a utility outfielder type who can’t keep his strikeout rate to a manageable enough level to tolerate his power output.

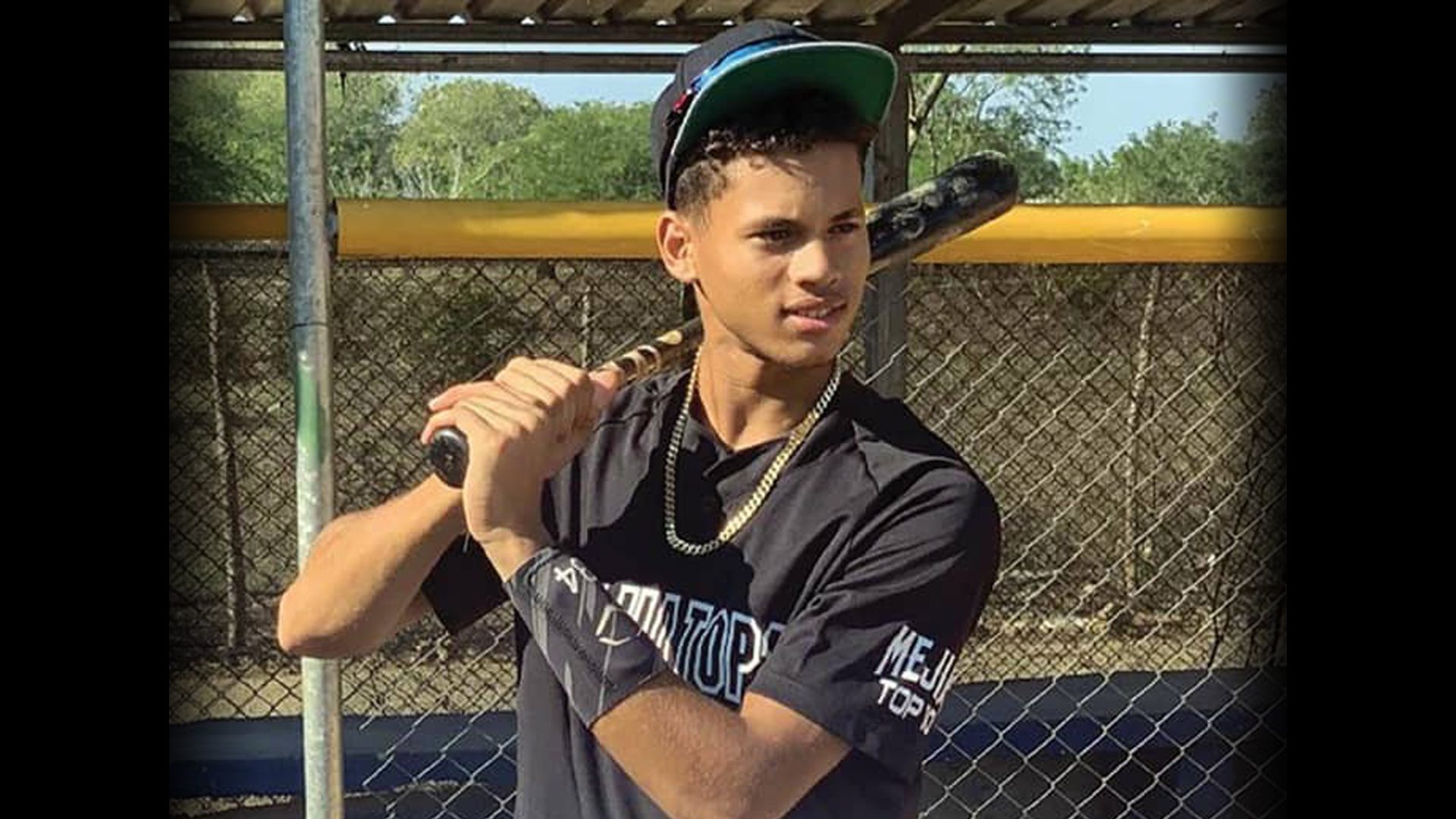

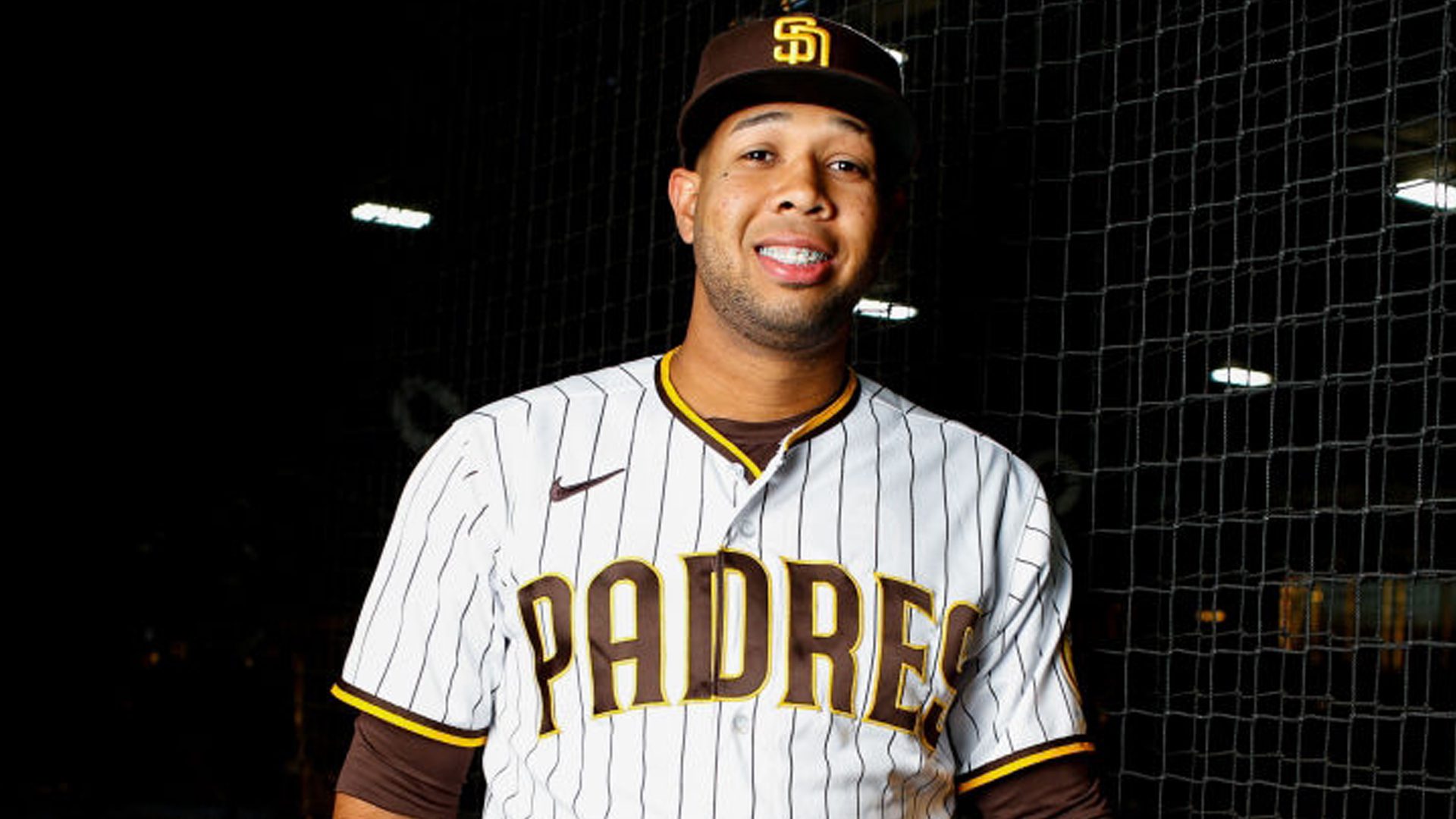

10. Reginald Preciado – SS/3B

Preciado is another core piece of the future on the Cubs Arizona Complex League team that has a lot of room to dream on his body projection. He stands 6-foot-4, joining the mix of tall position players littered across the Cubs complex team.

In our blurb on Alcantara, we mention the idea that weight gain doesn’t always convert one-for-one into in-game power output for young, toolsy hitters in the Arizona Complex League. This applies to Preciado as well, who isn’t hitting the ball as consistently hard as Alcantara, Canario or Caissie. While this is something to keep an eye on, scouts think one of his development points has to do more with lifting the ball when he makes hard contact rather than just adding weight to raise the ceiling on his batted ball data

Preciado is an aggressive swinger and much of the contact he makes is on the ground or a line drive, which stands in contrast to a player like Caissie who lifts his hard-hit balls exceptionally well. Preciado’s eventual weight gain will merely add the potential for more slugging. Whether he lifts those hard-hit balls consistently will be the difference between converting his hits into more advantageous production or underutilizing his tools.

Preciado’s defense fits more at third base or in a corner outfield spot, and he’s a below-average runner. But the overall profile of Preciado is still tantalizing because his feel for contact — even with his aggression — is so good. He has the potential to be No. 1 on this list after Davis graduates if he’s able to convert his weight gain into efficient power gains and lift the ball more consistently. At that point, the sky is the limit.

11. Brailyn Márquez – LHP

Márquez brings about our first discussion of the difference in projecting a player to start versus projecting them to be a bullpen arm. As discussed in the preseason Top 20, relievers graded as above average or even “plus” can be below starting pitchers and everyday players who are merely average. This is due to the cap on value even the most elite relievers can produce. And there’s an argument to be had that the way we construct “value” for relievers is inherently flawed given how viscerally meaningful late-inning outs can appear. (The majority of great teams in MLB still have designated closers who are used in traditional 9th-inning roles.)

Márquez, who hasn’t pitched competitively this year due to a shoulder injury, sits on the fence of the starter-reliever spectrum. That may seem to make it easy to place him in the multi-inning relief bucket, but given his pedigree and the electricity of his velocity, it’s hard to write him off as a starter. We just don’t presently have much of an update on the starter-reliever debate with him and injury alone — especially after a Covid-impacted season — isn’t a reason to think he’s purely a reliever all of a sudden.

Márquez throws a “gyro” slider, which will be discussed in relation to Anderson Espinoza just a few spots down on this list. But because of how Márquez releases the ball — from a true side-arm left-handed slot — it causes the pitch to look “sweepy” on broadcast cameras when in reality the pitch is not moving laterally at all. His slot alone gives left-handed hitters fits, and the gyro slider’s ability to be platoon-neutral, or be effective versus both handedness of hitter, makes the development of Márquez’s changeup gravy.

This year would have given more clarity on Márquez’s role long term, but for now, we’re still going off his brief MLB appearance in 2020 and past performance. There’s a chance he follows the Justin Steele path of development — impacting the bullpen at first before being stretched back out, something the Brewers have done to great success with nearly every one of their current starting pitchers. Whether he starts more games or enters in the 9th throughout his career will determine his ultimate value. This rank is a hedge somewhere in the middle of those two outcomes.

12. Christopher Morel – 3B

The slew of intangibles that Morel possesses — the most valuable of which being his on-field leadership — remain as strong as ever. Still just 22 years old, Morel has shown comparable power to his 2019 campaign with Class A, slugging 12 home runs and 10 doubles across 70-plus games this season. Not much has changed with his projection, there has just been an influx of talent in the Cubs system that pushes Morel down this list.

He projects for average to above-average in-game power, which puts him around 18-22 home runs per season. Mix that with a slightly below average hit tool, average speed and average defense, and while the combination of tools doesn’t jump off the page, the floor is high. His bat speed is plus, and the contact he makes is hard, posting some of the highest max exit velocity numbers in the Cubs system. This leaves open the possibility for a jump in production, particularly if he makes more contact as he ages and retains his current ability to scald baseballs. Consistent 20-plus home-run power isn’t far off, and that would make his profile a solid, regular starting third baseman.

Morel’s jump in strikeout rate — up to 29% this season — stands out, but he skipped over High-A with the cancellation of minor league baseball last season. Add in the context that Morel is aggressive at the plate, like Preciado, and the increase is right on par with what should be expected. If the plan is to have Morel play at Triple-A next season, he’s on track to debut as a 24-year-old either late next year or in early 2023.

13. Anderson Espinoza – RHP

Once a Top 50 prospect in all of baseball, Espinoza has undergone two Tommy John surgeries since signing with the Red Sox out of Venezuela back in 2014. The sample of pitchers who have had multiple injuries of this caliber before Double-A is infinitesimal. While one could extrapolate this to mean there is no precedent for a player like Espinoza having an impact in the majors, if data tells us anything, it’s not to predict anything based on small samples.

What we do know about Espinoza is that he throws four polished pitches. His fastball sits 95-96 mph and his best secondary is an 85-mph slider that could be classified as a true “gyro” slider. This means only a small percentage of the ball’s rotation contributes to the movement of the pitch. Instead, gravity does most of the work. To picture this, imagine a perfectly spiraled football thrown to home plate. It moves down only because of gravity. The spin of the football itself is not contributing to the movement of the ball. This stands in contrast to a pitch like a curveball, which is spun with an element of top spin, causing the ball to almost accelerate downward on its way to home plate. Gyro sliders are effective because they have a drop-off-the-table effect and can often neutralize left-handed hitters coming from a right-handed pitcher due to absence of the pitch moving in on a hitter’s hands.

Espinoza’s curveball and changeup — both of which grade out as above-average major league pitches — are merely icing on the cake that clearly projects him into a starting role if he can maintain his health. 2021 is his first season of affiliated baseball since 2016 and he has yet to throw more than 3.1 innings in an outing. Remove the two Tommy John surgeries from his track record and Espinoza has a case to be the top arm in this system.

14. Alexander Vizcaíno – RHP

Vizcaíno, along with Caleb Kilian, represent the two biggest pitching additions to the Cubs minor league system after the flurry of trade deadline moves. He stands a slender 6-foot-2 with room to add weight on his frame even though he’s already 24-years-old.

His role, like Márquez’s, is one that teeters between reliever and starting pitcher. This season, he hasn’t thrown more than 2 innings in an appearance yet back in 2019, he routinely threw 6-7 innings at Class-A in the Yankees system. The current narrative is that due to the deterioration of his control this season, a reliever projection is more likely, but it’s also easy to attribute any struggle throwing strikes to two factors: the layoff from game action last season due to the Covid-19 pandemic and an injury termed “arm soreness” that forced him to miss just over two months at the start of 2021.

Regardless of the role, Vizcaíno throws gas, sitting at 97 mph and touching higher. His changeup is considered by many to be his best secondary pitch, but the movement profile and velocity of his slider lines up with what effective modern sliders look like — hard with good total movement to the glove side, that holds the line of a pitcher’s fastball longer than sliders that sweep across the zone with greater horizontal movement. A pitch holding the line of a fastball longer means in theory it “tunnels” better. This is something that teams can now objectively measure with the recent installation of Hawkeye tracking systems.

Vizcaíno’s combination of three pitches is why it’s hard to write him off as a starter, even though some other prospect sites already have. If the modern closer becomes one who can mix more than two pitches — think Josh Hader and the emergence of his changeup in 2021 — then Vizcaíno lines up as a late-inning relief option. But his history starting suggests he could be used in a multi-inning role, or if the Cubs see three legitimate pitches, stretch him back out into a starting pitcher.

15. Ryan Jensen – RHP

Jensen throws what many call a “turbo sinker.” It’s a pitch that moves horizontally, or “runs,” more than 13-14 inches and is thrown in the upper tier of velocity for pitches with that kind of movement — 95 mph or harder. Though the exact definition can vary person to person, it’s a strong compliment. This innate ability to generate arm-side movement and throw hard carries over into his changeup, which he throws in the upper 80s. He also mixes in a slider and curveball, and the development of each have been key focuses of his player development this season.

His curveball has performed better in 2021 than his slider from a swing and miss and chase perspective and right now profiles as the stronger of his secondaries, but he is throwing his slider more. The intention with his slider is to increase the pitch’s velocity and retain the same movement profile. Right now the pitch has tight movement, which is a product of the velocity at which he throws the pitch, averaging 87-88 mph. That tight movement results in a few inches of glove-side cut and a little bit of “carry,” or vertical movement to help it hold the tunnel of the accompanying fastball longer (see Vizcaino’s blurb for more on this idea).

The downside of the turbo sinker is that because it’s such a good pitch, especially in the minor leagues, there’s little reason to throw anything else if your goal is simply to get batters out. But development is arguably more important than just winning games in the minors. The Cubs are trying to give Jensen experience and goals that will make him as good of a major league pitcher as possible, rather than a good minor league pitcher. This can sometimes skew the results of an outing to look terrible but provide value to the pitcher from a maturation and development standpoint.

The likelihood of some major league role for Jensen is high given the quality of his stuff and the data suggesting his combination of velocity and ability to generate plus arm-side movement on everything is uncommon. Whether any of his secondaries approach a quality high enough to push him off throwing his turbo sinker and four-seam fastball over 50% of the time or more will show whether he becomes a full-fledged starting pitcher or acts in some kind of modern, multi-inning role.

16. Caleb Kilian – RHP

The Cubs acquired Kilian as one of two pieces in the Kris Bryant trade. Kilian was an 8th-round pick of the Giants in 2019 and has shown one thing in particular throughout his minor league career: he pounds the strike zone. In just over 100 minor league innings, his walk rate is an incredible 1.1 per 9 innings, and he’s relinquished only two home runs.

Kilian’s primary fastball is a sinker that sits around 93 mph on average, with a curveball and cutter acting as his primary secondary offerings. His extension down the mound is exceptional and would put him inside the 80th percentile among all major league arms. He also throws a four-seam fastball, changeup and slider, all of which carry movement profiles and average velocities that suggest he could actually be a 6-pitch starter in the future.

But Kilian’s “stuff” is average rather than many on this list who sport multiple plus pitches. He has a distinct “tuck” of the ball when his arm swings back, similar to Cubs legend Rick Sutcliffe or Dodgers legend Don Sutton, that may help his deception. But nothing jumps off the page on the movement profile of all his pitches. For that reason, it remains to be seen how Kilian fares against better hitters in the upper levels of the minor leagues. For now, getting away with zone-pounding and pitches advanced for their level will work, especially if hitters have to plan against 5-6 offerings.

Perhaps the Cubs acquired Kilian with the intention of taking certain pitches in his repertoire and emphasizing them, or changing others to perform better on “stuff” metrics. This would resemble what the Cubs are intending to do with White Sox reliever Codi Heuer, acquired in the Craig Kimbrel deal. With Heuer, they want to create two distinct fastballs — a four-seamer and sinker to allow him to neutralize left-handed hitters. Changing the shape of a pitch, the seam orientation with which it is thrown or separating two pitches into clearly distinct offerings, are all common goals of modern pitch design sessions.

Every organization that acquires a player has some plan of attack that they believe will make that player better. The difference in Kilian’s mix between the Giants and Cubs will show what the Cubs intend to do with the 6-foot-4 righty.

17. Cole Roederer – OF

Roederer played 20 games this season for High-A South Bend before landing on the IL. It was announced in July that the left-handed hitting outfielder underwent Tommy John surgery on his throwing arm. The good news is that he is expected to be ready for Opening Day 2022. This could slow down his development timetable slightly, but given his improved discipline and performance in a small sample of High-A games, there’s a chance he starts at Double-A Tennessee next season and continues to show a high-walk, average-strikeout profile.

Roederer has played the majority of his games in center field throughout his minor league career, but he grades out as a below-average to average defender there. Many scouts see him moving off the position to center field, letting a stronger defender — like Crow-Armstrong — play the position. The weight he has added since being drafted out of high school in 2019 and the subsequent jump seen in his raw power projects him to have enough of a bat to hold down the strong side of a platoon in left field. His offensive numbers project similarly to Morel, although Roederer is a more patient hitter at the plate. But Morel’s batted ball data is much stronger, aligning the third baseman more with the modern approach to what offensive talents at the major league level should look like.

There is a high chance Roederer has some role at the major league level for the Cubs’ next postseason run, it’s just a question of how much upside there is in his profile.

18. Kohl Franklin – RHP

The difficulty in ranking Franklin stems purely from the lack of competitive pitches thrown since 2019. The Cubs’ 6th-round pick in 2018 had been out all season with an oblique injury. The assumption is that Franklin is still being built back up in Arizona and could hopefully return to game action sometime before the minor league season ends. If not, he’s a candidate for fall instructional league, after which we’ll have a better assessment of how he looks on the mound and can more confidently place him on this list.

In 2019, Franklin primarily threw a fastball and changeup, with sparse usage of a curveball. His fastball sat around 92-93 mph. He joins the ranks of Cubs pitching prospects — Wicks, Vizcaino and Jensen — who have changeups that currently grade as their best secondary offering. We were overly aggressive on Franklin on our preseason list, due to reports from his summer camp performance and his delivery. This leaves the door open for a jump back inside the Top 10 if he returns strong late this year or if there’s reason to suspect his velocity is back to ticking above his usual 92-93 mph.

19. Ismael Mena – OF

There is a debate in scouting circles as to whether Mena will move off of center field. If he moves off the position, the offensive standard required to man a corner outfield spot jumps dramatically, especially in an organization with multiple other corner outfield prospects that we project to have impact profiles (most notably Caissie and Alcantara).

There is no indication as to which group makes up the majority in this Mena debate among Arizona-based scouts. What is undeniable is that Mena has made numerous great plays in center field. So the idea that he moves off the position assumes that his weight gain slows him down, which is another idea that has some holes. More mass takes more energy to move, but with the modern advancements in strength and conditioning, it’s likely that strength gains could make a player more explosive and able to plateau his speed based on how his lower-half moves and develops.

There’s more value in Mena being a center fielder, simply because his bat isn’t as advanced or projectable as Caissie, Preciado or Alcantara. He is aggressive at the plate and doesn’t produce a ton of hard contact, but his ability to make contact combined with his aggression puts him in a window of low walks and low strikeouts. Most teams will take that in a center fielder. It’s probably not a perennial All-Star profile, but if Mena continues to hit and play solid center field defense, he has a role on a major league team.

20. Burl Carraway – LHP

Carraway takes the final spot in our Top 20 rankings because of his pure talent. He’s a smaller-than-normal left-handed reliever with a fastball that sits 95-96 mph and tops out higher. He sequences that with a curveball that breaks viciously downward in the 78-79 mph range. That’s all he has and really all he needs to stymie hitters. An interesting note would be if the Cubs ever choose to have him develop a slider, primarily because the number of leverage relievers with sub-80-mph curveballs — even with as big of movement as his has — is small.

Carraway is also a great player to reference when thinking about some of the advanced pitching concepts in baseball, one of which being the spectrum of how a pitch approaches the plate. Hard, four-seam fastballs with big vertical movement (“ride” or “carry” are both interchangeable with vertical movement in scouting parlance) are thrown up in the zone because the angle at which the ball crosses the plate is flatter than if it were to be located down in the zone. Data shows these pitches with flat approach angles are more effective up in the zone, primarily because it’s difficult for a hitter to get “on plane” with the pitch, or match the incoming trajectory of the ball with the path of their swing.

There are multiple variables that influence how “flat” the approach angle of a pitch is, two of which Carraway excels at with flying colors: the actual vertical movement of a pitcher’s four-seam fastball, or how much it resists gravity’s attempt to make the pitch drop, and the angle from which the ball is released (which can also be be phrased as “outlier release characteristics”).

Carraway’s rank on this list also acts as a stand-in for other leverage relief prospects in the Cubs system that have a case for Top 20 placement, he’s just the best of the bunch. Ben Leeper is 1B to Carraway’s 1A, if he adjusts the natural cut on his fastball. And Manuel Rodríguez has a good case to be 1C in this mix. Remember that the difference between No. 20 on this list and who would’ve been number 30 is relatively small. If a few things break in one player’s favor, they’ll build an admirable case to be included in our 2022 preseason update.

Honorable Mention

Max Bain – RHP

If you ask a scout why a pitcher didn’t make it, you’ll receive one of many responses, most of them measurable: “he never developed a quality breaking ball” or “he couldn’t throw strikes.” The far more interesting reason a prospect doesn’t make it, perhaps because it rarely becomes public, is because of their makeup (intangibles, like work ethic, growth mindset or their ability to make adjustments). Makeup can also be the reason prospects exceed their perceived ceiling.

Bain has 80-grade makeup, the highest rate you could give for the characteristic. It will play a role in his ability to make adjustments at higher levels and hastens his ability to achieve team-designated player development actions. His understanding of advanced pitch design concepts is greater than that of some coaches. His initiative to invest in himself long term with an understanding of his own biometrics, biomechanics and command tracking tools are just the surface of evidence supporting his desire to measure, react and improve.

Bain throws five pitches and sits 94-95 mph on his four-seam fastball. He learned his changeup grip earlier this year and the swing-and-miss rate on the pitch is already exceptional given the infancy of the offering. His slider has a small amount of top spin, which gives it the appearance of a curveball on camera, but his curveball is distinguished enough from his slider in its vertical movement that both pitches live in his repertoire effectively. The last of his five pitches is a cutter, which is a lesser-used offering but one with plus velocity that tunnels off his four-seam fastball well at the top of the zone.

His results at High-A in just his first season of affiliated ball leave much to be desired, but again, converse with Bain about what he needs to tweak and there’s a direct answer, with a plan of how to get there and a maturity to contextualize individual moments in the greater scheme of his process. His Aug. 11th start in Fort Wayne was an example of what things will look like if everything clicks.

Chase Strumpf – 2B

Strumpf, Roederer and Nico Hoerner all have very similar body types, standing a sturdy 6-foot to 6-foot-1 with relatively maxed-out bodies. Strumpf is a pure second baseman, where he is a below-average to average defender. His profile is built on his advanced college bat which has moved quickly through the Cubs system due to an evolved understanding of the strike zone.

The ceiling on his offensive output will see somewhere around a .260-.270 average with above-league-average OBP and sub-20-home-run power. Also like Roederer and Hoerner, most of his home-run power comes from hitting to his pull side. But there is some major league role to be had with Strumpf, it’s just a question of how much ceiling his overall package has. Because he does not have many tools outside of his ability to hit that project better than average, there is probably a cap on his overall value. But like many other names inside the Cubs Top 20, the floor is high.

DJ Herz – LHP

Herz is another in what is becoming a long line of Cubs pitching prospects who favor changeups as their main secondary offering. But his best pitch is a 92-93 mph fastball. For a while, scouting grades on fastballs were essentially just describing the velocity of the pitch (an average or “50-grade” fastball was just one that sat around 91-92 mph). But in the modern age of data, we have a better understanding of why one fastball with just average velocity can “play up” and produce results better than the raw velocity would suggest.

This is the case with Herz, who has a four-seam fastball with an above-average amount of vertical movement, allowing it to drop less than a hitter expects. Combine that with his advanced ability to locate the pitch where it will be successful — at the top of zone, see Carraway’s blurb for more info — and his 41% strikeout rate at Class A Myrtle Beach isn’t surprising.

On top of a fastball and changeup, Herz also has a curveball. The movement profile of the pitch is much tighter than a pitcher like Carraway’s curveball, dropping over a foot less. This suggests there might be a point where Herz is asked by the Cubs to try and throw his primary breaking ball harder and he evolves into a fastball-changeup-slider pitcher.

If the result of that cue to throw harder is a pitch that retains some of his curveball’s present sweep and can sit above 84 mph, most pitch grading databases would probably suggest it has a greater chance of missing bats at the major league level. There is probably a strong chance he evolves into a four-pitch arm as well, with both his curveball and slider proving effective.

Hertz’s motion is distinct, with a big leg kick and hip lead towards the plate before he strides, similar to Marlins legend Dontrelle Willis. There are a lot of variables to watch with Herz — breaking ball evolution, velocity, control — and if a few of them pop in the next year, he will be a Top 20 prospect in this system.

Riley Thompson – RHP

Thompson is currently sidelined with a shoulder injury and joins Márquez, Franklin and Michael McAvene as pitchers without game action since 2019. He also joins Wicks, Vizcaíno, Franklin and Herz as a pitcher who uses his changeup as his primary offspeed pitch. While it’s hard to gauge expectations for Thompson coming off a Covid year and an injury, the raw elements of his repertoire are deserving of a mention

Thompson’s fastball acts a lot like Carraway’s in that he throws with an extremely over-the-top motion, allowing the ball to be released from his hand with a direction of spin that leads to high vertical movement numbers. The perplexing thing in Thompson’s data is that this pitch wasn’t located in the optimal part of the zone for the characteristics of the offering to prosper. Thompson put the ball towards the bottom or middle of the zone more often than not, where elevation on a pitch with this much vertical movement would net better results (see Carraway’s blurb for more information). For some pitchers, this change in location is a difficult switch to flip, especially given how large the average pitcher with great command misses their target by.

If Thompson can solve his fastball location — perhaps he did during the shutdown, we just don’t have game confirmation yet — and pair that pitch with a curveball and changeup, which both grade as future average offerings, he projects to be a back-end starting pitcher rather than a fastball-reliant reliever who has a funky over-the-top release.